Squadron Supreme is a often ignored classic.

It was a groundbreaking superhero story. It took archetypal characters to their organic extremes. Every action had consequences. Change was real and long lasting. These were sophisticated stories featuring complex moral and philosophical issues, told through the genre of brightly colored super beings.

It wasn’t Watchmen.

The comic in question was The Squadron Supreme, a 12 issue limited series written by Mark Gruenwald with pencils by Bob Hall, John Buscema, and Paul Ryan, and inks by an all star cast. It debuted in September of 1985, a full year before Watchmen. There are a lot people (including me), who consider it an unsung classic, deserving of the type of recognition that Watchmen gets. So why is it overlooked?

A Brief History of the Squadron Supreme

The Squadron Supreme were created by Roy Thomas and John Buscema, although it would be fair to say they were actually created by Thomas and John’s brother, Sal. See, the Squadron first appeared in Avengers #85 in 1971 as good versions of a team that Thomas and Sal had introduced just two years earlier in Avengers #69: the Squadron Sinister. Each team had the same four members (although the Supreme version had an additional four), but they weren’t the same. One was bad, one was good.

If you’re confused by that, you’re not alone. Even Marvel’s own production office couldn’t keep the two teams straight, advertising the “Squadron Sinister” on the covers of two issues of the Avengers that actually featured the Squadron Supreme.

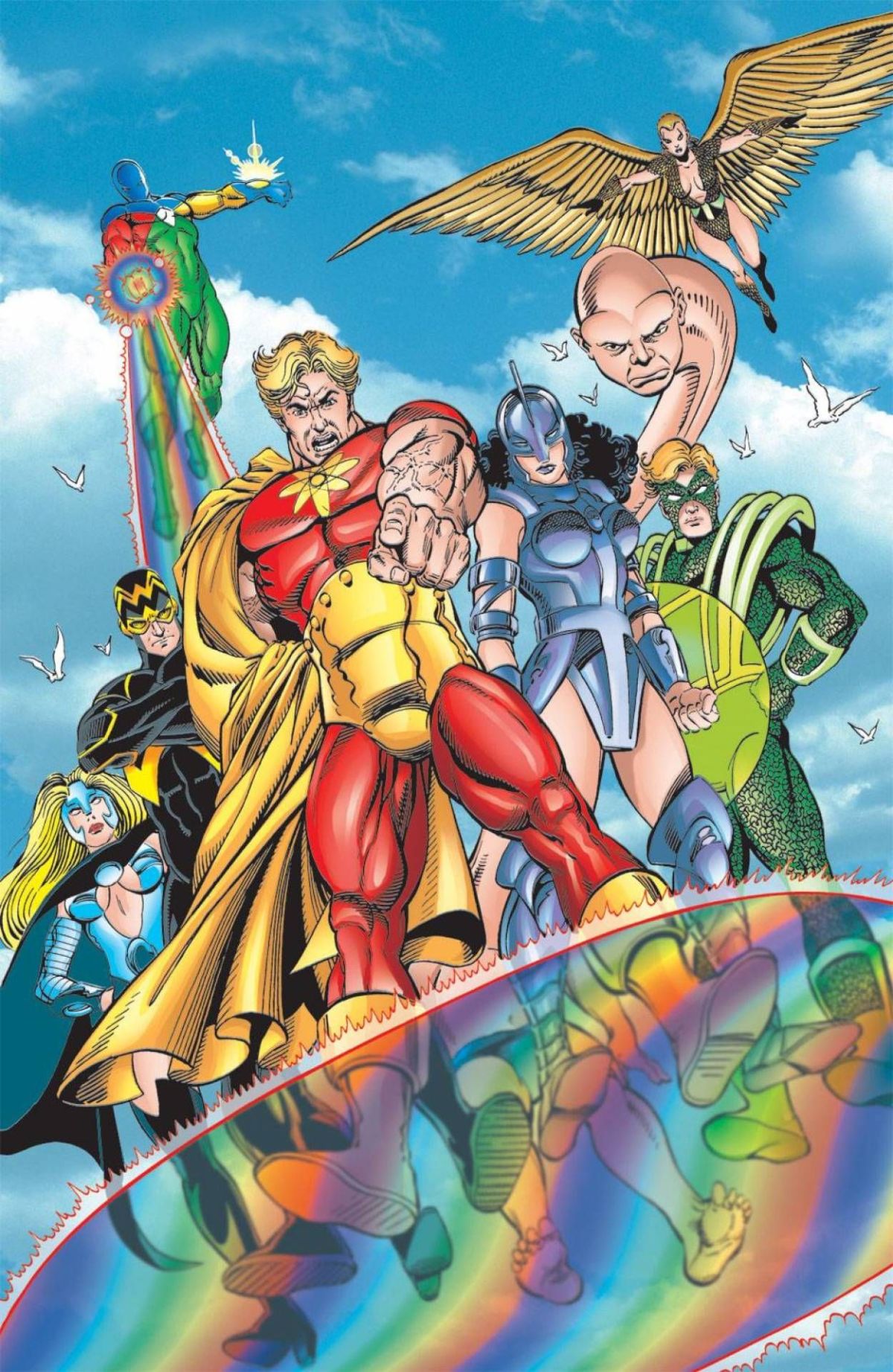

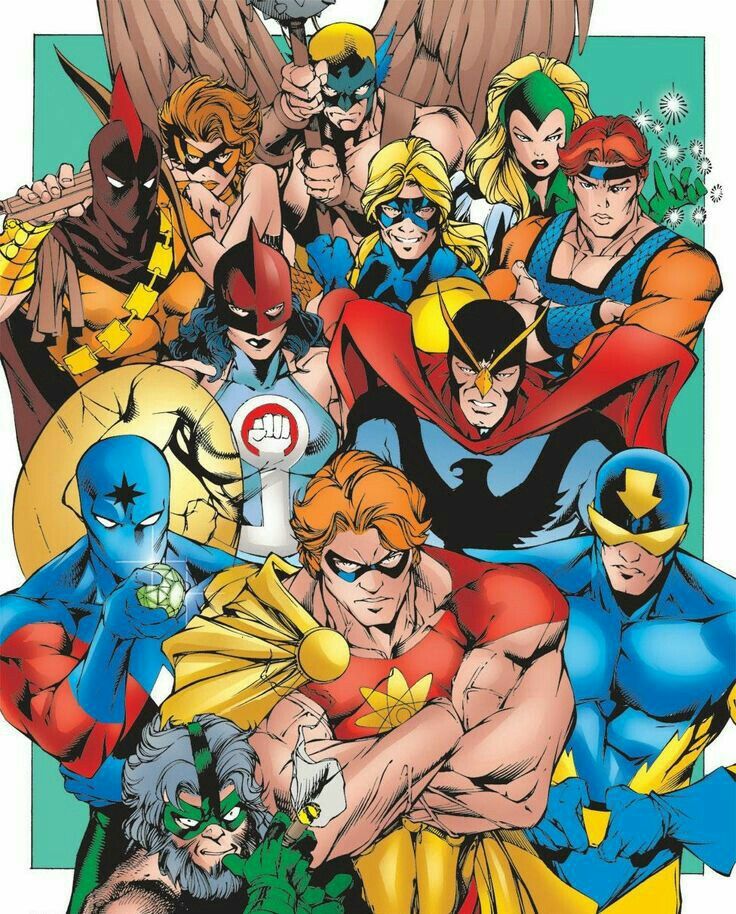

Anyway, both teams were created as analogs for DC’s Justice League of America. The common members of the two Squadrons were Hyperion (Superman), Nighthawk (Batman), Whizzer (the Flash), and Doctor Spectrum (Green Lantern). When the Squadron Supreme first appeared, their line-up also included Lady Lark (Black Canary), a different character named Hawkeye who would later go by Golden Archer (Green Arrow), Tom Thumb (the Atom) and Cap’N Hawk (Hawkman). It’s kind of interesting that those were the additions, as opposed to versions of the remaining Justice League founders (Wonder Woman, Aquaman, and Martian Manhunter).

The Squadron Supreme would make a few more appearances in the Avengers, as well as showing up in an issue of Thor and Spider-man. But their big story line would come with an extended arc in the Defenders. The ranks of the team would fill out here as well, with the additions of Power Princess (Wonder Woman), Amphibian (Aquaman), Arcana (Zatanna), and Nuke (Firestorm). Missing from the ranks is the Skrullian Skymaster (the Martian Manhunter) who would be briefly shown as a founding member in the first issue of the Squadron Supreme series, but would only be revealed in the Squadron’s entry in the Marvel Handbook (at least until the follow-up to the follow-up of the Squadron’s series).

Now, a word about Nighthawk. Nighthawk is Kyle Richmond. On our world (the 616 Earth of the Marvel U), he was a Defender. But here’s the thing: the Defender known as Nighthawk wasn’t actually of our world! He was, in fact, the Nighthawk from the Squadron Sinister who switched sides and ended up joining the Defenders!

I know, right?

But it’s the Squadron SUPREME’s Nighthawk that is important. In the Squadron’s next appearance, Kyle Richmond had become president of the United States of the Squadron’s world. He was soon taken over by the Overmind, who used Richmond to turn the U.S. into a paranoid police state. The Overmind himself was under the influence of Null the Living Darkness, but that’s neither here nor there. The important bit is that the Overmind also took over the Squadron. The Defenders managed to free the Squadron and together they defeated Null.

And that was it.

Because No One Demanded It

In the sixteen years since the Squadron Sinister first appeared, the Squadron Supreme had only made a handful of appearances in the Marvel U, none of which had any lasting impact. It’s hard to imagine there was much of a fan movement to get them their own series.

There also wasn’t much from the Defenders story that would suggest a Squadron Supreme story needed to be told. They’d been taken over by a supervillain, but what superhero hasn’t? But if there was a core idea behind the Squadron’s series, it was to extrapolate the bigger picture from something small. Gruenwald took the germ of the Defenders story and turned it into a virus. The Squadron had been controlled by the Overmind for quite some time, and they’d been busy. They’d helped to build the United States into a fascist country that then spread across the globe by invading and occupying the rest of the world.

But then the Overmind went away and oppressive order turned into complete chaos. The world hadn’t actually ended, but the Squadron Supreme’s earth was about as post-apocalyptic as you could get.

With the world in shambles, the Squadron Supreme decided to get proactive.

But this isn’t The Authority style proactive. No, the Squadron decides to set themselves up as a super power. Federal governments remain, but in reality everyone answers to the Squadron. The Utopia Project initially focuses on feeding the world, building homes, bolstering the economy, and dismantling the military. After all, what good are stealth bombers or even nuclear bombs when you’ve got Hyperion, the stand in for Superman running around?

In a world full of superheroes, there are always supervillains, they always seem to escape from whatever prison they’re locked in. So to break this endless cycle, the Squadron Supreme come up with the Behavior Modification Process. Basically, it’s a machine that changes a person’s mind, removing their criminal impulses and replacing them with a desire to do good. Before Zatanna, Dr. Strange, and Nick Fury began mind wiping, the Squadron Supreme was altering people’s brains.

And then they got rid of death, or at least created world wide system to put people into deep freeze until they could be cured or brought back.

Not every member of the Squadron is on board with their program, though. Nighthawk leaves the team from the start, determined to find a way to stop is former compatriots from ostensibly taking over the world, even if they have the best intentions. He argues that they should be helping humanity, not commanding it.

The series ultimately follows two narratives: The Squadron’s efforts to create a Utopia and Nighthawk’s plans to oppose them. The two story lines come to a head in the finale which was, at the time, one of the most brutal comics I’d ever read.

Name a political issue and there’s a reasonable chance the Squadron Supreme limited series dealt with it. And each issue featured actual change, be it a new development in the Squadron’s plans, the death of a character, or the escalation of a moral dilemma. This was a big time ideological battle taking place in the pages of a superhero comic. It may have lacked the subtlety of a certain other 80s comic that rewrote the rules of superheroes, but it was just as deep.

I’m not doing the series justice, in large part because this lacks context. Superhero stories like this just didn’t exist back in 1985, even though they would become all the rage after Watchmen was released. But the Squadron Supreme series came first, yet isn’t showing up on a Time magazine list any time soon.

The Watchmen Factor

The thematic similarities between the two series are striking.

Both books feature superheroes taken to their extreme ends. In the case of Watchmen, it’s breaking them down to the fragile human beings that they really are. As many of said, it’s a deconstruction of not just the characters, but the genre. If anything, Squadron Supreme is pumping the characters full of steroids, taking the idea of superheroes to the other end of the spectrum, where they place themselves above the rest of the world. In Watchmen, they are down in the gutters with the rest of us, manipulating events in the background. In Squadron Supreme, they are overt, taking over the country and forcing their will upon us.

These behaviors carry over to the way the story is told. Both comics feature secret plots to prevent horrible events from happening, but in Watchmen those plans are kept secret from both the characters and the reader; we only as much as they do. In Squadron Supreme, we see it all. Nothing is hidden. And why would it be? It’s the actions that are important, so we need to see them, as opposed to Watchmen where the driving force is the mystery. If we had all the information in Watchmen, it would lose momentum.

Even these secret plans are set opposite each other. Ozymandias’ goal is to prevent the world from falling into chaos brought by a third World War, a nuclear World War. Nighthawk’s goal is to prevent the world from becoming imprisoned by the extreme order brought by the Squadron Supreme. The beginnings are the same way. When Watchmen opens, there’s a certain status quo, one that involves all (but one) vigilante having retired and Richard Nixon serving yet another term as president. The death of Comedian up ends all of that, introduces chaos into the equation, chaos that eventually pushes the world to the brink of WWIII. In Squadron Supreme, the world has already fallen into chaos, but the Squadron Supreme decides to create order.

It’s also interesting to note that both books deal with analogs of other characters. Moore wanted to use the Charlton superheroes, but was famously told to create new characters instead. Moore wanted to use recognizable characters so that the opening had some emotional resonance. DC obviously didn’t want to ruin their newly acquired IPs. It was an odd decision, though, given that Watchmen doesn’t take place in the mainstream DCU, or even on an alternate Earth, as by this point DC had done away with such things. Captain Atom, Blue Beetle, et al. would have been perfectly fine in the DCU even if Moore had used them.

The fact that Watchmen took place in its own reality, set aside from the DCU, at a time when DC had gotten rid of alternate realities, increased the profile of the book. This must be something special if DC were willing to create a superhero book that was completely removed from the rest of their line.

By that same token, Squadron Supreme was firmly entrenched in the mainstream Marvel U, even if the series took place on an alternate Earth. It had roots in the Avengers. It was seen as just another Marvel comic.

Opposite Ends of the (Doctor) Specturm

Ultimately, the Squadron Supreme and Watchmen are as different at the two men who wrote them, Mark Gruenwald and Alan Moore.

By the time Squadron Supreme debuted, Mark Gruenwald had been working for Marvel for 7 years. He was initially hired as an assistant editor and had moved up the ranks quickly. He was perhaps best known as the editor of the Avengers line of comics, although he would later become synonymous with Captain America, a title he wrote for 10 years. Gruenwald’s run on Cap would feature incredible highs (everything leading up to #350, really) and incredible lows (the newly returned Captain America armor, for example), but the length and depth of his time on the book would ultimately make him one of Captain America’s premiere creators.

Gruenwald wrote superhero stories. He edited superhero stories. He was known as the guy who knew every piece of obscure continuity in the Marvel universe.

Leading up to Watchmen, Alan Moore had made a name for himself in the U.S. with his impressive run on Swamp Thing. He’d also penned the classic Superman stories “For the Man Who Has Everything” and “What Ever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow?” but the bulk of his work had been on a sophisticated horror title that had parted ways with the Comics Code Authority and would eventually be labeled “Suggested For Mature Readers.”

To say that Moore was coming at Watchmen from a different direction than Gruenwald was approaching Squadron Supreme is an understatement.

The two publishers were in very different places as well. Marvel was being run by Jim Shooter, who had hammered the company into a well oiled machine of family friendly superhero fare. Marvel wasn’t in the habit of taking risks at this point in its history. The fact that the Squadron Supreme even happened was impressive, but the fact that it took place in an alternate reality made that possible.

DC, on the other hand, was being run by Jenette Kahn, who had already broken new ground with Frank Miller’s Ronin and the Dark Knight Returns, not to mention the new direction Moore had taken Swamp Thing. Post-Crisis on Infinite Earths, DC seemed focused on publishing a variety of content that appealed to a wide range of ages.

So when DC, hot on the heels of The Dark Knight Returns, announces that the guy who rejuvenated Swamp Thing would be releasing a brand new limited series that was meant for mature readers, people take notice. The same could not be said for the guy who writes Captain America releasing a new series starring minor characters from an old Avengers story line.

Squadron Supreme is pure superhero story and embraces those elements; everyone runs around in spandex and capes like it’s perfectly natural. There are big, bombastic battles. No one will ever think this is anything other than a superhero comic, even if it’s a truly phenomenal one.

Watchmen simply has some superhero dressing. It’s not the story of supremely powerful beings living among us. It’s the story of regular humans doing insane things for a variety of reasons. It’s just as much a murder mystery and political thriller as it is a superhero story. It’s science fiction. Watchmen stands out from the metric ton of superhero comics being published by the Big Two every month.

Watchmen made its characters less super; Squadron Supreme made them more. They appear to be diametrically opposed, yet did so much to change the way superhero stories are told.

The Post-Gruenwald Era

After the Squadron Supreme limited series, Gruenwald and artists Paul Ryan and Al Williamson abused the Squadron some more with the “Death of Universe” OGN. This particular adventure took place in space, and somehow on their return trip, the Squadron ended up in the mainstream Marvel U. They kicked around for a bit before the Avengers finally sent them home. Sadly, they returned to a very 90s universe in “New World Order.” They would eventually appear again in the Exiles series.

There was also an attempt at creating another version of the team, spear headed by J. Michael Straczynski. The goal, it seemed, was to make them more realistic. It didn’t turn out too well.

The team’s highest profile member is Hyperion, would play a major role in Jonathan Hickman’s Avengers run, although Hickman has stated that this is yet another version of Hyperion and not the “Gruenwald version,” as he called it. That’s unfortunate, as this Hyperion is the only survivor of a destroyed Earth, and there’s a part of me that would like to see the Squadron’s earth wrapped up for fear of anyone doing any more harm to the team.

But the original Hyperion did eventually pop up, part of the fall out from Secret Wars. A new team is formed consisting of characters who have lost their alternate realities. The concept in and of itself is fine, but the series was uninspired and ended after less than two years.

The Squadron Supreme had their moment to shine in a complex, epic limited series. If you love superheroes, you owe it to yourself to track down this truly groundbreaking run.