I was prepared to hate Wonder Woman: Earth One.

The early commentary online wasn’t kind. Grant Morrison seemed to be setting the bar awfully high for himself in his interviews, and Yanick Paquette is an artist whose work has always had a cheesecake element to it. How would they avoid the pitfalls of two men writing about an island full of beautiful lesbians? How does this not turn into a male fantasy when Morrison has been very clear about embracing Wonder Woman’s bondage past? I can’t imagine even attempting such a thing, particularly given how scrutinized it’s sure to be. We’re talking about two men attempting to tell a story of empowerment featuring the most famous female superhero in existence.

Early copies slipped into the world and we saw images of chains and women captured by men and an overweight character seemingly mocked for her appearance. It had all the makings of not just a train wreck, but an offensive train wreck.

Instead I read the best origin of Wonder Woman that I have ever seen.

First, a caveat of sorts: there are a few moments in this graphic novel that aren’t as clear as perhaps they could or should be, which then lend themselves to being what I would consider misread. I think there is textual support for my reading and I’ll get to that as I go through the book, but these moments are there and should be acknowledged.

But let’s start with a high level look, because I have a feeling that’s going to trip up a fair number of readers.

Traditional storytelling structure is based on the male orgasm: there’s the build-up, the climax, and the denouement. This is a simplified version of Freytag’s pyramid, which features five storytelling beats: exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, denouement. It’s perhaps easier to view as set up, action, climax, fallout, ending. Freytag’s theory was meant to be applied to Greek and Shakespearean drama more so than modern drama, which has simplified it to three parts, ala the three act play. The vast majority of stories follow this pattern, even if it’s modified a bit. It is the standard by which stories are judged by publishers, agents, movie studios, etc. In many cases, a lack of a three part structure automatically disqualifies a book or script.

This is a Wonder Woman story, and a story about the Amazons, so Morrison smartly denies the traditional structure. There is no real single climax to be found here. The focus isn’t on a specific, determined path from point A to point B. Instead, we have several moments that all seem equally as important. It makes for a completely different kind of reading experience, but one which carried me quickly through the book. This was less a single big story and more a series of connected events with one, overarching theme. It could be the most important decision Morrison made when writing Earth One, as it sets the tone of the entire book. It’s composition is at odds with traditional, patriarchal stories.

Along those same lines, there’s very little violence in Earth One. There are roughly ten pages of actual violence in this entire, 144 page comic, all of which happen at the beginning. Not surprisingly, that violence is the result of the actions of men. The fact that less than 10% of this comic features violence is staggering given the content you’ll find in a traditional superhero comic. But this is a Wonder Woman comic and she’s an ambassador of peace. That is her goal, even if she also happens to be the ultimate warrior. That’s part of what makes her so interesting: she’s a highly trained, very powerful warrior who is trying to inspire peace.

The structure of the story and the lack of violence are essential because they reflect the main character. Instead of trying to force the ultimate female hero through the prism of the male adventure story, we get something that is true to Wonder Woman, true to the environment that created her.

That male lens would also dictate that this story be filled with scantily clad supermodels in suggestive poses with other scantily clad supermodels. And it’s not unreasonable to expect at least some level of cheesecake given that Paquette draws attractive women. I think part of this reputation comes from his work on a books like Codename: Knockout, but that book featured both cheese and beef cake, and was specifically created to feature titilating poses of men and women. The ability to draw attractive people shouldn’t be an issue here, really, so much as whether or not they’re being drawn in way that seems unnatural for the sake of appeasing the male gaze.

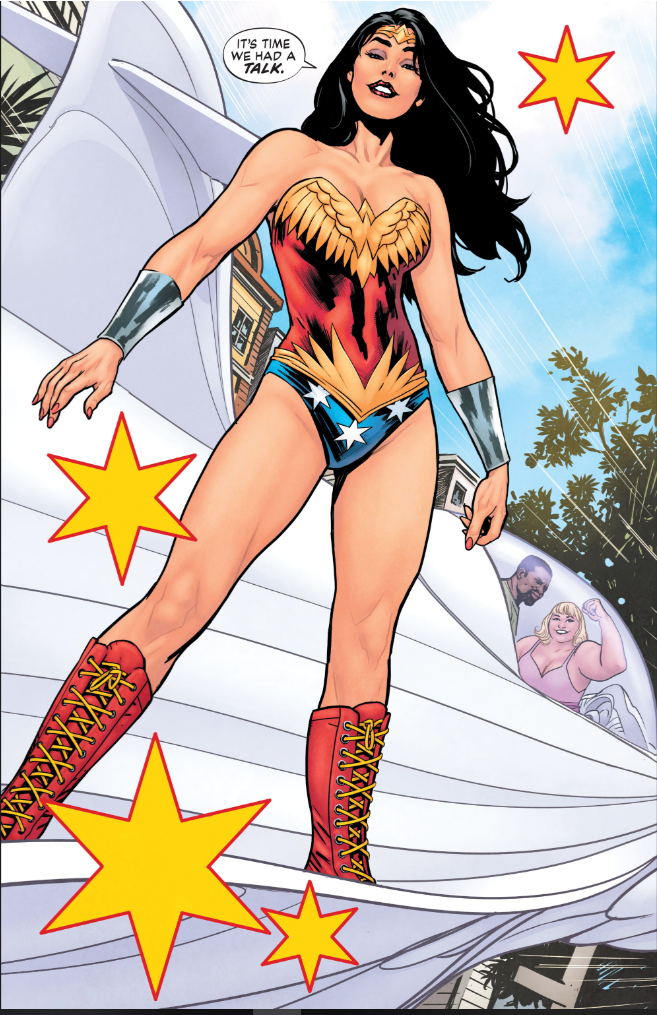

But Paquette avoids that. Yes, his Amazons are beautiful, but they’re also Amazons: it’s part of the initial concept, that they’re subjectively perfect in every way. But at no point are they placed into positions or drawn from angles that would serve to exploit their attractiveness. There are no typical comic book panels of just the posterior and no one wears a skirt that happens to be a bit too short. Yes, Diana’s anatomical proportions seem to defy nature, but she and the Amazons wear clothes you would expect a group of active, trained warriors to wear. Their outfits aren’t just practical, they’re clearly informed by their Greco-Roman roots.

Paquette embraces those roots. He incorporates that cultural aesthetic into all aspects of the Amazons, going so far as to intersperse the initial scene with the types of images you’d find on the walls or on pottery in ancient Greece. The suggestion here is that the Amazons are, from the very start, immortalized in Greco-Roman history, something that would come up again later in this book.

Paquette also makes every single character in this book look unique. It’s a stunning accomplishment, really, if you just consider the overwhelming number of Amazons he has to draw. But all of them, from their faces to their hair to their attire, are distinct from each other. I can’t even fathom the amount of time that had to have been spent on even background characters in order to pull this off; it’s unbelievable. It makes Themyscira seem like a place where everyone is free to express herself however she may choose. It emphasizes the fact that this culture is far more advanced than our own.

For all the credit that Morrison is going to get for this book, it’s just as much Paquette’s. This is career elevating work for him; it might be for Morrison, too, if that’s possible.

If Morrison owes much of the success of this story to Paquette, then Paquette owes much of the success of the art to colorist Nathan Fairbairn.

There’s a very clear, very obvious trap lurking in WW: Earth One with regards to the colors: the book is split between two worlds, that of the utopia of Themyscira and that of our modern day real world. This is a trap because it would be very easy for any colorist to simply portray the former in bright, positive colors and the latter in dark, dreary colors. But Fairbairn has made a career on telling stories with his colors. Neither world is as simple as being all light and all dark. There are degrees at work, degrees which make these worlds fully realized, even beyond the words and the line art.

While Themyscira contains darkness, there’s a subtle difference. The colors are softer and more distinct; even the hunt that takes place at night has a playfulness and calmness that underscores the Amazonian society. This is a place where everyone is treated fairly, a virtual utopia, where the night is dark, but not scary. The colors during the day are bold and bright, but complimentary, both creating a sense of individual freedom while embracing unity. There’s a thematic cohesion to Paquette’s designs and Fairbairn takes that to the next level with his colors.

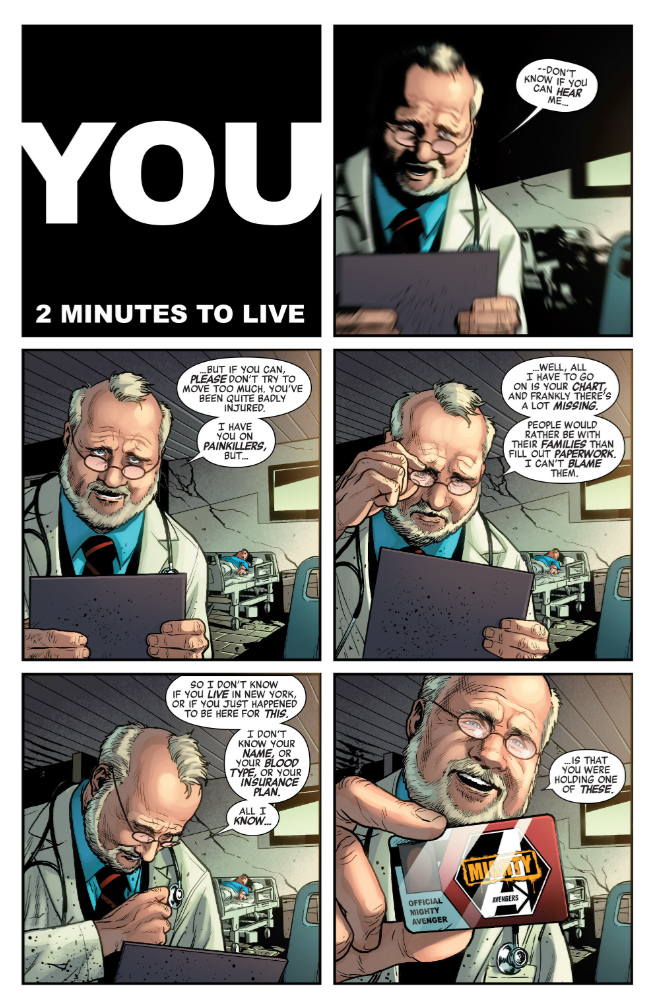

On the other hand, our modern day world isn’t just starkly dark and depressing. Yes, it’s not as bright as the world of the Amazons, but this isn’t the Sin City movie, for example. Man’s world has variation, but unified by a roughness, as if it hasn’t completely fallen into darkness. And that, of course, is the point: man’s world can be saved, it just needs someone to save it. And while Wonder Woman is painted in relatively muted tones when she initially arrives, when she returns at the end of the book she is as bright and bold as we would expect. She’s here to save the day.

That isn’t to say that WW:E1 is perfect. There are two problems in particular that, to their credit, stem from an overreach on the part of Morrison and Paquette.

The first is Steve Trevor. While changing his ethnicity raised many eyebrows, there’s a very clear reason for it within the story. Wonder Woman goes to America and finds a country that has marginalized all but the straight, white men. To prevent Trevor from being a part of the very institution that WW would be facing off against, he could no longer be white. His gender and orientation are somewhat essential to is role (as he is a man setting foot on Themyscira and he is attracted to Wonder Woman), but his race makes no difference. This new iteration changes that and to good effect.

The problem, then, is in making Trevor African American. The only goal is to make him something other than white. The choice to make him black is loaded with problems, if only due to the imagery involved. On Themyscira, submission to another is considered a form of trust, of love, but to ask the sole black character in this book to wear bondage gear seems tone deaf. I wouldn’t go so far as to call it offensive, but the idea is never really addressed or fleshed out, so we simply have Diana trying to convince Steve to wear clothing meant to evoke images of slavery. On one hand it speaks to Diana’s ignorance of this new world and Steve’s place in it, but that’s as far as it goes. And given that Steve could be any ethnicity other than white for his new role to work, it’s hard to understand why Morrison decided he should be black.

At the very least, it kicks you out of the narrative, just like the introduction of Etta.

Etta is, compared to every other female in this book, overweight. And while her introduction to the story is when she gives her testimony at the trial of Wonder Woman, chronologically her first appearance comes on a bus ride with her sorority sisters to South Beach for spring break. It comes with one of her sisters suggesting that she ate the food they had gathered to feed the less fortunate. In other words, it feels like she’s being body shamed.

Fortunately, Morrison quickly undercuts this. Etta isn’t fat, not in her eyes, and those are the eyes that matter. In fact, she isn’t shy about how perfect she thinks her appearance is; she is full of self-confidence, even when one of her sorority sisters is insulting her. It doesn’t matter to her. Etta is above it. She knows herself and she’s happy with who she is. This initial introduction wasn’t an indictment on her, but on the other women, on how they treat those who don’t conform to society’s ridiculous notions of beauty.

Even Wonder Woman herself gets in on the act: “Oh, what has man’s world done to your bodies…” But in the panel before that we don’t just see Etta, we see the typical comic book (typical magazine) female form: beyond petite and not at all healthy. Wonder Woman isn’t commenting on Etta alone, but all of the sorority girls.

But commenting on female beauty standards is going to be a tricky situation even when not written and drawn by men. There’s just too much to unpack to adequately address in a entire graphic novel, let alone a few pages. The fact that Morrison and Paquette don’t shy away from the issue is commendable, but they were never going to really be able to do it justice. On the other hand, ignoring the issue would have been equally as problematic, so they were painted into a bit of a corner no matter what. This is the price you pay for deciding to tell a story about the most recognizable female super hero in the world.

Ultimately, though, Wonder Woman: Earth One is an ambitious retelling of the origin of one of the world’s greatest superheroes. It succeeds far more than it fails, and even when it does falter, you can appreciate the attempt. I appreciate the fact that Morrison and Paquette took chances on this book and it’s clear from the work that those chance energized them.

Let’s hope we get a second volume so they can do more.

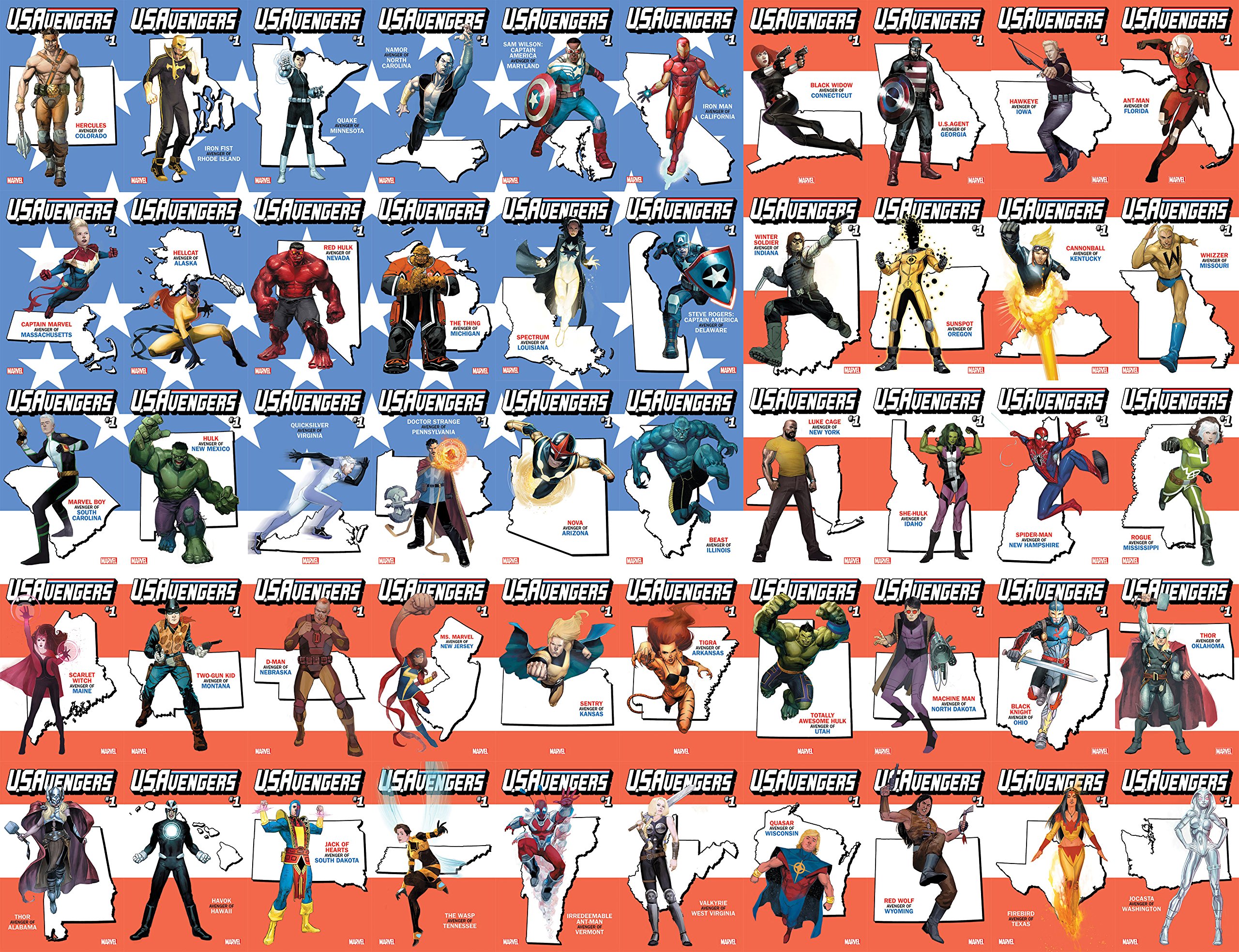

The stories are strange, too, in that they seem disjointed, not at all like what we saw in New Avengers which had a very clear through line. This series seems broken up into parts, from a rollicking adventure with time travelers, to big monster fights, to yet another crossover, to a strange alien adventure with the cast of Archie.

The stories are strange, too, in that they seem disjointed, not at all like what we saw in New Avengers which had a very clear through line. This series seems broken up into parts, from a rollicking adventure with time travelers, to big monster fights, to yet another crossover, to a strange alien adventure with the cast of Archie. Still, Ewing has fun with the cast when he can and any book that features a good amount of screen time for Sunspot and Cannonball is always welcome.

Still, Ewing has fun with the cast when he can and any book that features a good amount of screen time for Sunspot and Cannonball is always welcome.