Is there a more universally reviled moment in Marvel’s history that the debut (and subsequent crash) of “Marvelution?”

For the uneducated, back when Marvel was pumping out a ton of comics and involved in all sorts of corporate level shenanigans, the powers that be decided the best way to monetize the line would be to break it into five groups.

I suppose it makes some sense in a corporate lizard type of way: why have just one interconnected, money making line of comics when you can have five, interconnected, money making lines of comics?

The groups were:

Marvel Heroes (Fantastic Four, Avengers, and Avengers related books

Spider-man (all Spider-books)

X-Men (all the X-books)

Marvel Edge (see below)

Non-Marvel Comics (Licensed books, Epic Comics, etc.)

You can see some of the problems right off the bat. Aside from the fact that expanding to five universes would expand Marvel’s line even beyond what it already was, there’s the fact that part of the appeal of Marvel is that their books are interconnected, not divided into lines.

Then there’s the matter of all those books that don’t fall neatly into any of these five groups. The New Warriors, for example, got stuck in the Spider-man group and were then forced to take in the Scarlet Spider as a member to more closely associate themselves with the other titles.

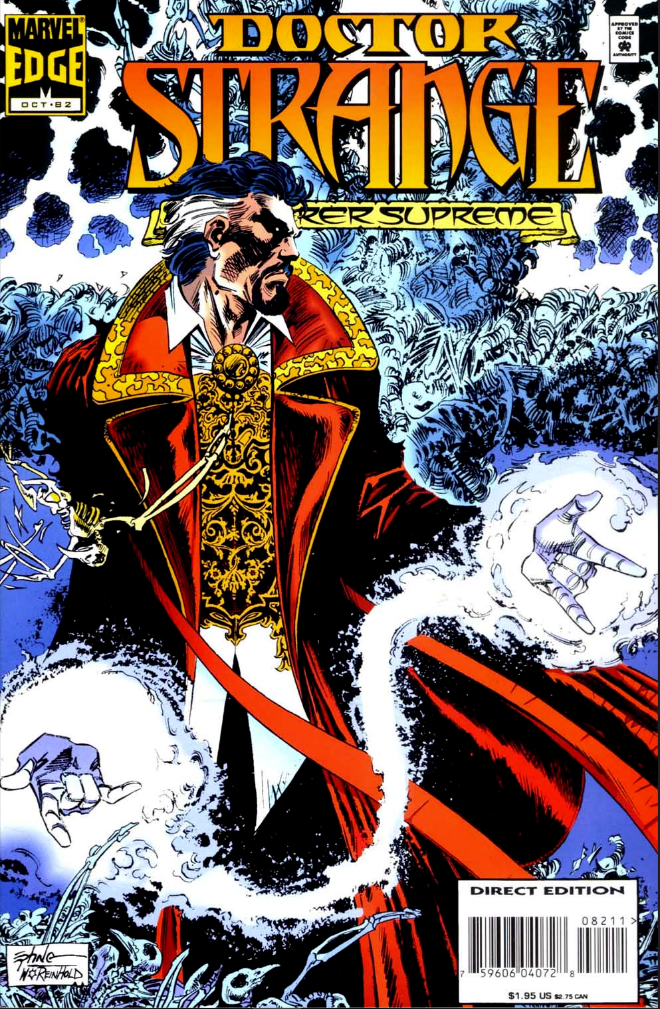

What about the Hulk? This was before the Marvel movies, before people started thinking about him as an Avenger again. Or what about Dr. Strange? He wasn’t an Avenger. He wasn’t a mutant. He had little association with Spider-man.

Marvel Edge became the catch all for titles that couldn’t be shoehorned into the other groups.

The ongoing books:

Daredevil

Dr. Strange

Ghost Rider

The Punisher

The Hulk

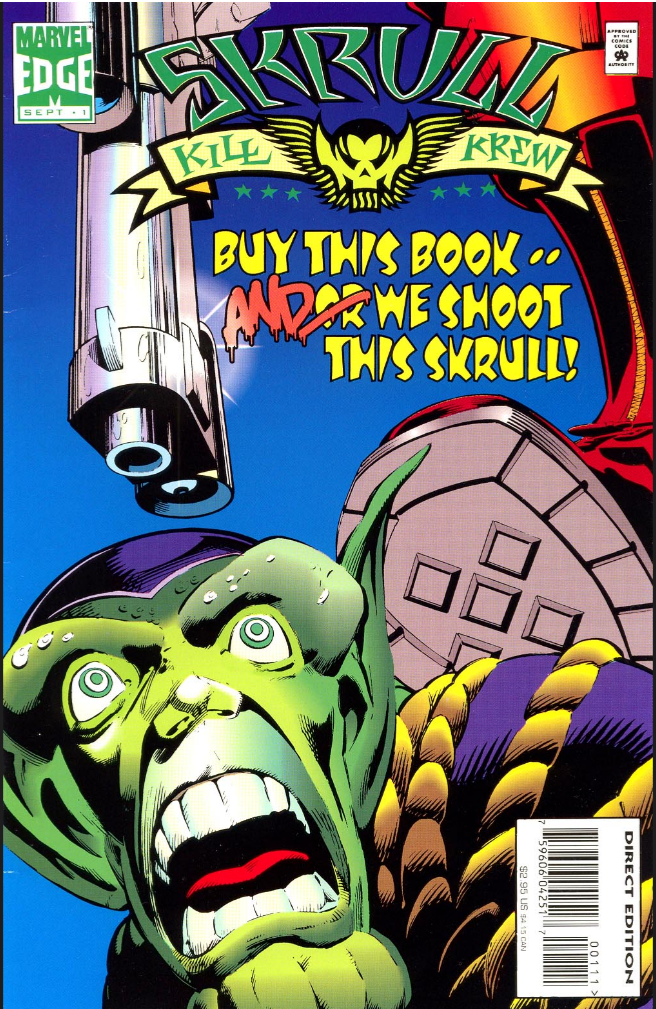

There were also a handful of limited series spinning out of those titles, including the first Skrull Kill Krew series. There as also a monthly book called “Over the Edge” that rotated characters each month. It was part of Marvel’s 99 cents line made to attract new readers and offer something for those who had been priced out of regularly Marvel titles.

You might be able to connect the dots on the first four titles in that list above — you’ve got the street level characters in Daredevil, the Punisher, and Ghost Rider. And Dr. Strange regularly operates in the same space as Ghost Rider. But how does the Hulk end up in that group?

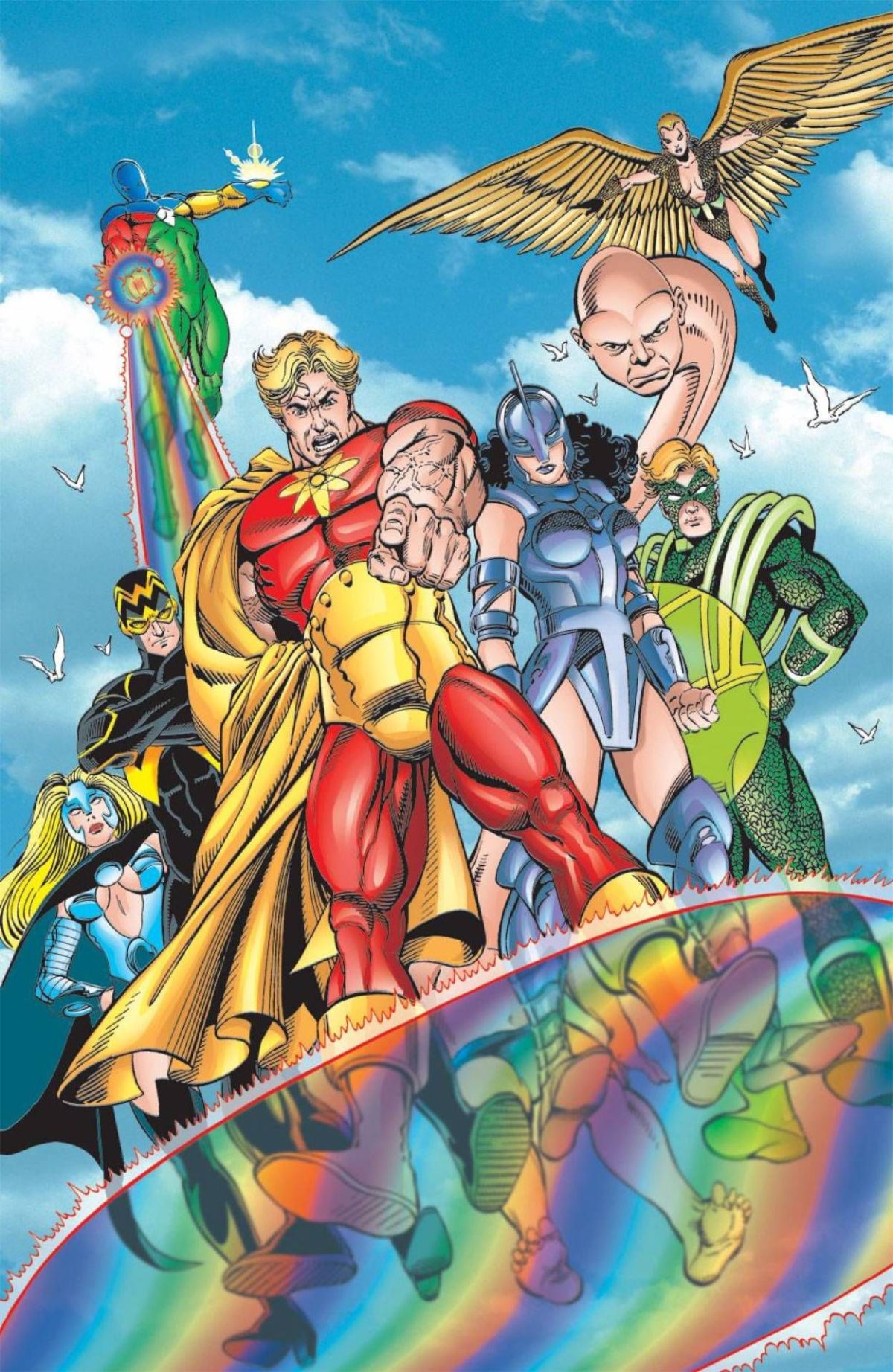

Since Marvel Edge is a new line entirely and not just a clear definition for a group of books (ala the X-books or Spider-books), it started the way you would expect: with a crossover event.

It’s called “Over the Edge” and it starts exactly how you would expect, with a double sized, chromium cover special called “Double Edge Alpha.” It would then continue in an issue of the other main books (not including The Punisher, as his series had ended, but he would get a new one stemming from this event) and finally ending in, you guessed it, “Double Edge Omega.”

If you judged the line simply by this crossover (which, to be honest, I did) you would think Marvel Edge is horrible. Many of these issues barely connect with the story in part because these characters just don’t operate in the same space. Not only that, but the story itself is too thin to support this many issues.

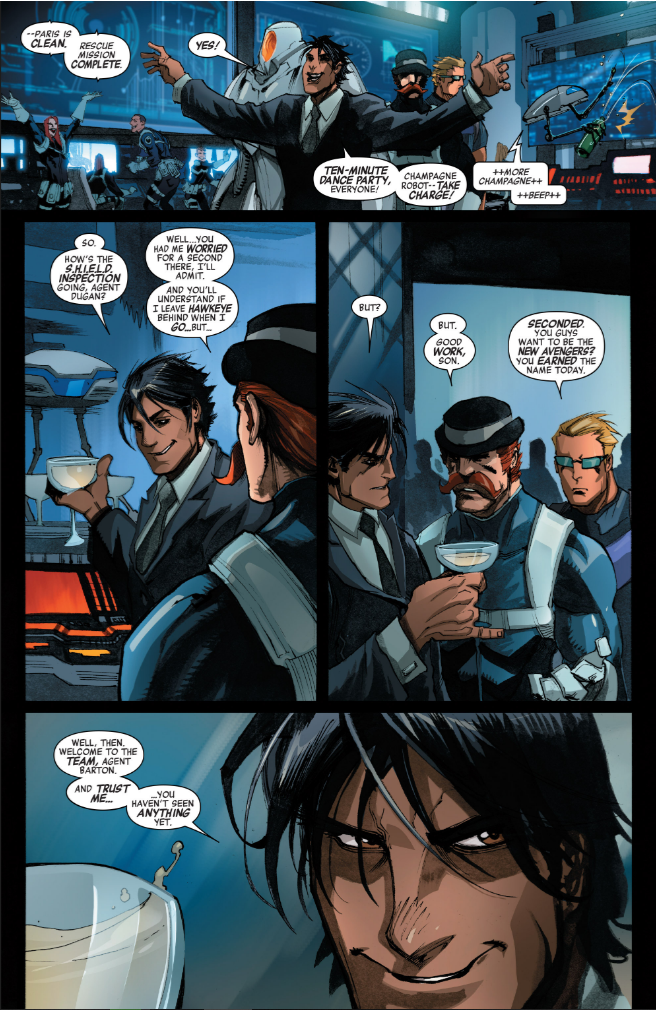

Basically, SHIELD captures The Punisher, who is then brainwashed by a rogue agent to be believe that his family was killed by Nick Fury. The Punisher breaks free and begins hunting down Fury and anyone close to him.

Using SHIELD as the framing device for this crossover is a strange move given that none of these characters have much of a connection with that organization. There had to have been a better thread to weave throughout these books, but maybe this was a testing ground for a future SHIELD series.

Regardless, the event ends with The Punisher killing Fury and being sentenced to death.

Dedicating the first month of the line to a crossover seems like a good idea until you realize that the line only lasts 8 months. Any connective tissue formed in that initial story didn’t last very long.

The fact that Marvel Edge only covers 8 months does, however, make it easy to go back and read every issue with the Edge logo on it.

Some highlights from the line:

- Salvador Larocca’s art on Ghost Rider is great. He’d really started to develop his own style on this run.

- Ron Garney’s art on Daredevil is also great. Garney is one of the most underappreciated artists working. He’s assisted by some nice stories from JM DeMatties, although I will admit that DeMatties goes a little overboard on the captions.

- Mark Buckingham on Dr. Strange is great, too. But he’s saddled with some uninspiring stories by a number of different writers.

- The new Punisher series is pretty fantastic. The gist of the story is that Frank’s execution was faked by a mob boss who wants him to take over his crime family. Seeing Frank compromise his rather ridiculous black and white view of the world is a lot of fun, even if he does resort to wearing his costume way, way too much. It’s written by John Ostrander, so no surprise as to the quality. It’s mostly drawn by Tom Lyle.

- Angel Medina takes over on art on the Hulk and I’ve always enjoyed his work. He’s a great fit for the Hulk.

There are, of course, some low lights, too.

- The Hulk series is treading water. It seems like Peter David is just trying to come up with new variations on the traditional Hulk, which worked for the first bunch of years he was on the book, but at this point feels like grasping at straws.

- Dr. Strange and Ghost Rider are fairly boring, art notwithstanding.

- The Typhoid Mary limited series is bad. It’s really bad.

- The Skull Kill Krew limited series does not hold up at all and, if anything, is borderline offensive. The idea that a race of creatures are considered universally evil and deserving of the death penalty is a horrible, horrible take, and the characters are incredibly unlikable.

In the end, having a shared corner of the universe for the “street level” and supernatural characters in the Marvel universe is a solid idea, but the characters chosen were hard to connect. With stronger creative teams and a more focused reason for the books to be connecting, this is something that could actually be pretty good.

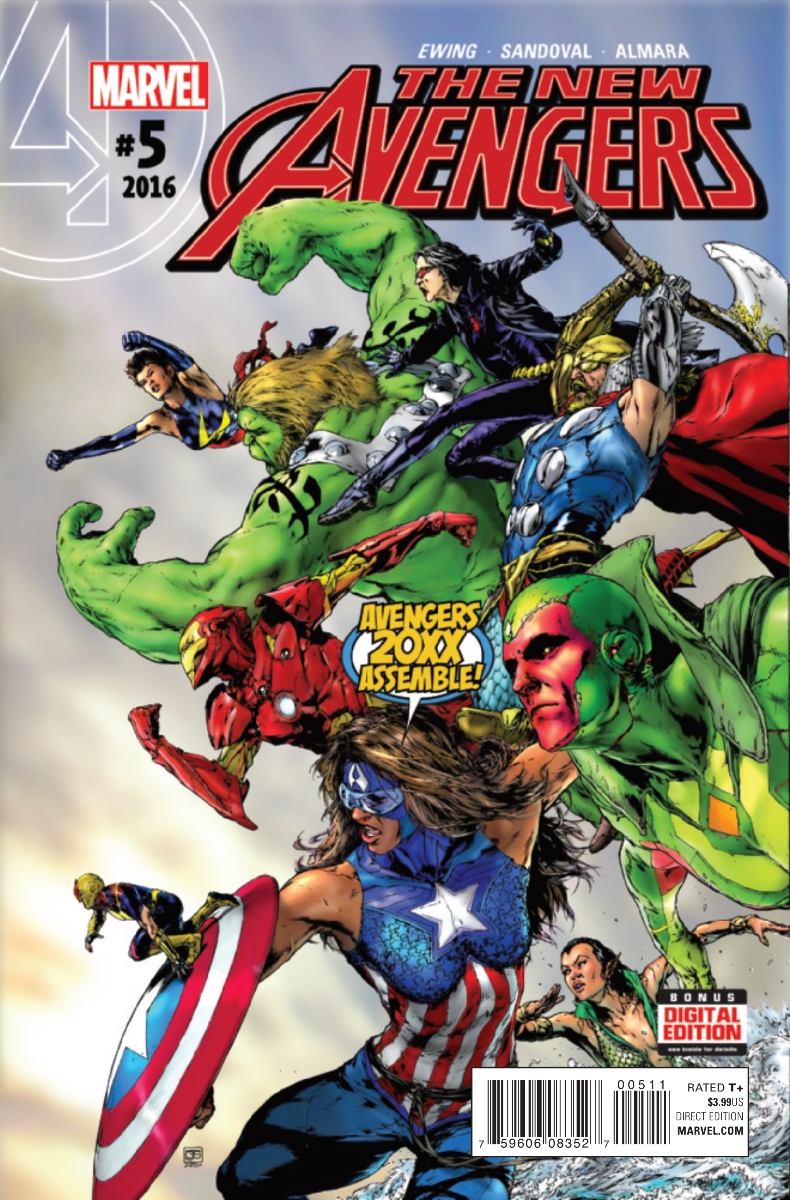

The stories are strange, too, in that they seem disjointed, not at all like what we saw in New Avengers which had a very clear through line. This series seems broken up into parts, from a rollicking adventure with time travelers, to big monster fights, to yet another crossover, to a strange alien adventure with the cast of Archie.

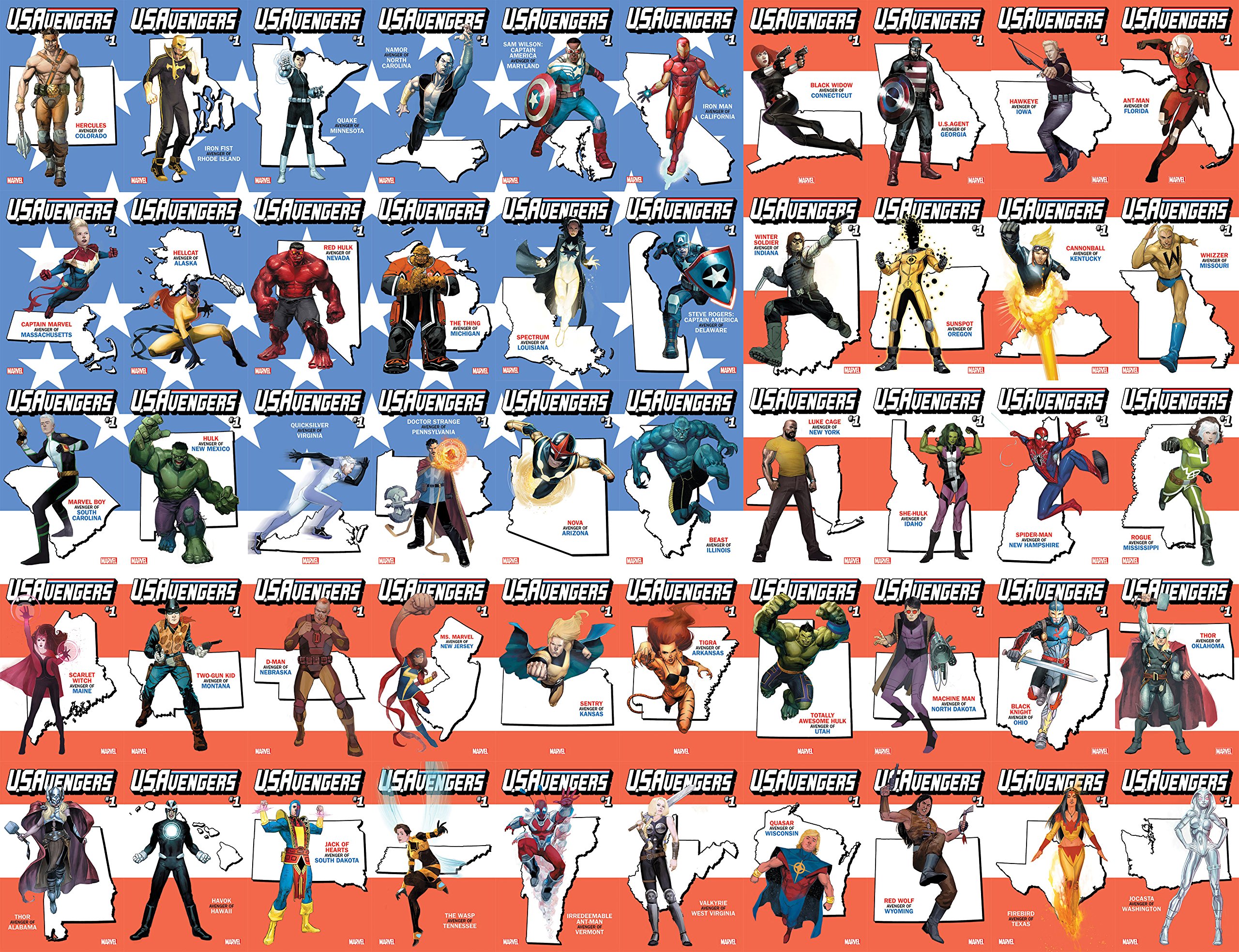

The stories are strange, too, in that they seem disjointed, not at all like what we saw in New Avengers which had a very clear through line. This series seems broken up into parts, from a rollicking adventure with time travelers, to big monster fights, to yet another crossover, to a strange alien adventure with the cast of Archie. Still, Ewing has fun with the cast when he can and any book that features a good amount of screen time for Sunspot and Cannonball is always welcome.

Still, Ewing has fun with the cast when he can and any book that features a good amount of screen time for Sunspot and Cannonball is always welcome.