Let me start with three opinions:

1. Super Sons (Jon Kent and Damian Wayne) was fantastic and I miss both the series and the relationship that those two characters had. I loved that imaginary stories from decades earlier suddenly became real in the DCU.

2. The actual story that aged Jon was bad. It made no sense that Clark and Lois would let him go off with Jor-El even if Lois was going with him (which made no sense, either) and Lois certainly wouldn’t have left Jon with Jor-El by himself. The whole thing made no sense, but that’s often how Bendis writers: he has a point A and a point B and he forces a line in from one to the other, even if it doesn’t work.

3. I love the Legion of Superheroes, so if points 1 and 2 were necessary for 3, I figured I could get over it.

The problem is that it’s become clear that 1 and 2 weren’t remotely necessary for 3. And, honestly, 1 and 2 have made 3 worse.

Who Is Jon Kent?

Part of the problem is that teenage Jon Kent hasn’t been developed at all. The extent of his development has been that he’s less childish than he was before, I guess?

The idea that Jon is responsible for the United Planets is a bit of a stretch and completely unearned. Superman doing it? Yes, totally makes sense. It makes so much sense, in fact, that the story of the UP forming had to eventually focus on Superman. Scores of other alien races would ultimately ignore Jon’s involvement when they tell the story, because who the hell is Jon? But everyone knows Superman.

But somehow the story of Jon inspiring the UP lasts until the far future, so the Legion comes to get him. Jon goes to the future and…does nothing. So far in the Legion series he has done nothing at all, other than break a rule by going to get Damian and bringing him to the future.

Jon is there for exposition, for backstory. But even that has taken forever. And, again, it’s unnecessary. He’s not acting as a POV character because he’s freaking Superboy. And hundreds if not thousands of comics have managed to give the backstory of superhero teams without a supposed POV character.

Honestly, the series would probably be covering more ground if it weren’t for Jon’s involvement.

Superboy and the Legion of Super-heroes

When Geoff Johns brought the “original” Legion back in 2008, he made a few changes to limit some of the elements of the team that required fixing every few years. The biggest and best change he made was how Superboy was a member.

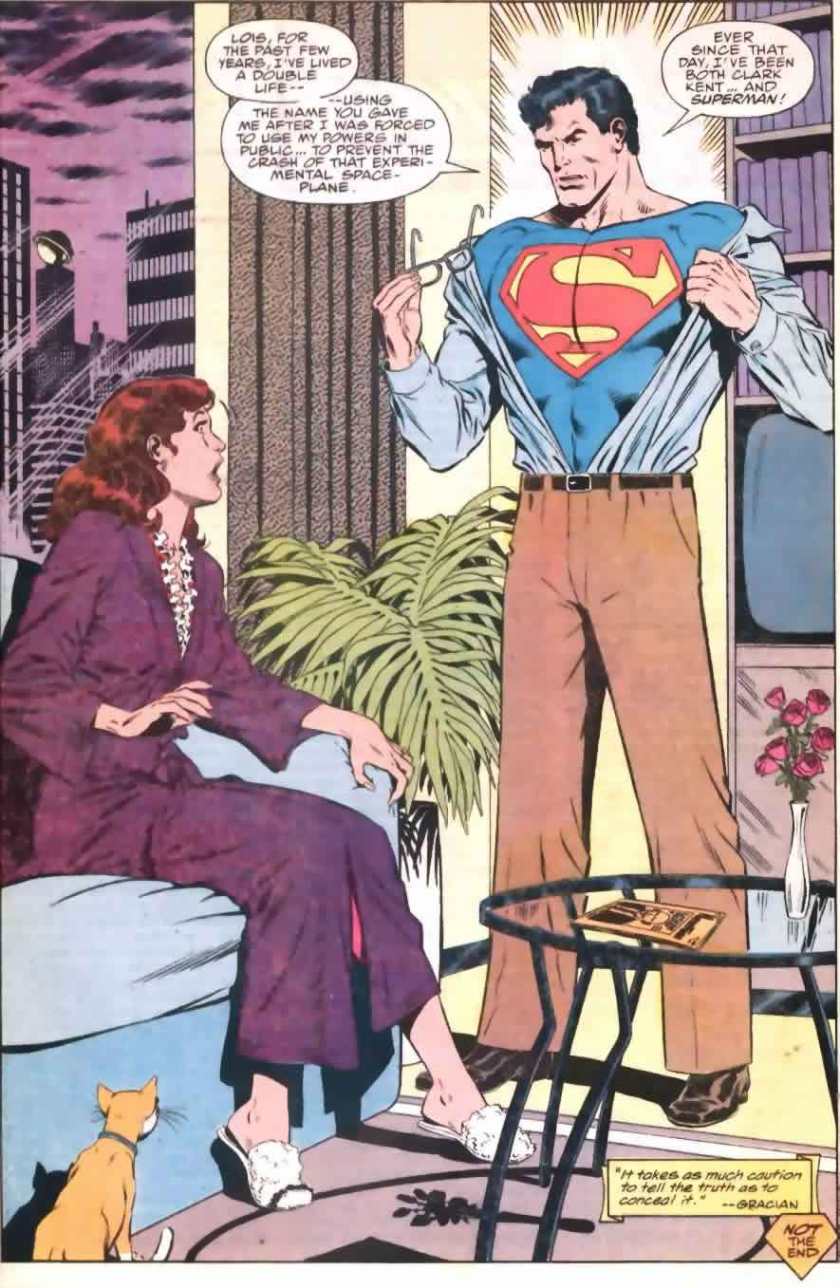

When the Legion first appeared, Superboy was, well, Superboy. Clark Kent flew around Smallville having adventures as the Boy of Steel. When he grew up, he’d be Superman and fly around Metropolis as the Man of Steel and somehow no one put the two together and figured out who he was.

That’s not really the kind of thing that would have worked in modern comics, so post-Crisis Superboy went away and Superman never put the tights on until he was in Metropolis.

This was a problem for the Legion, given that their history was so intertwined with Superboy, their inspiration. The Superboy they knew wasn’t the real Superboy, or at least not the Clark Kent who would grow up to the Superman in the main DCU reality. It’s a story that the Legion would revisit multiple times in order to provide more clarity and make it more urgent.

Reboots would point to the adult Superman as inspiration for the team, but it didn’t have the same feeling. Whether it made sense or not, Legion is and will always be connected to Superboy.

So when Johns brought back the “original” team, he made some changes (thus putting “original” in quotes). One of those changes was to address the Superboy issue. He did so in a surprisingly simply and poignant way.

Clark Kent had met them when he was a teenager, just as the original story went. But he wasn’t Superboy at the time. He went with them into the future and had adventures, but did none of that in our time. This allowed him to maintain his secret identity.

Honestly, you could make the case that he used the Superboy costume in the future and just kept it hidden in the present until he was an adult. It wouldn’t be that much of a stretch.

The idea of lonely teenage Clark Kent finally finding some friends who all had superpowers is fantastic. Emo Superman is a characterization that writers go back to again and again and it always feels at odds with who Clark Kent is. So why not explain why the lone survivor of another planet who could barely touch people without hurting them didn’t become an anti-social outcast?

What About the Story?

What does a teenage Jon Kent do for the comics? What doors does he open up, what stories does he introduce that could not have existed before?

As noted above, he wasn’t necessary for the Legion and he shouldn’t have been necessary for the formation of the United Planets.

What about all those stories about Lois and Clark dealing with a teenage son? That’s easy: what stories? Not long after aging Jon up, he was sent to the future and for some reason hasn’t returned, even though it’s time travel and he could literally return the moment after he left.

I suppose we needed a POV character to meet the Legion of Superheroes, but has that even mattered so far? Did we need Jon Kent for exposition? Origin stories are revealed all the time over the course of a story without the need for a single character to be taught everything.

But the Super Sons? The Super Sons are unique. The concept itself was formerly set in the “imaginary story” reality of the DCU. But it was suddenly real! Or, as real as they can be in a fictional universe.

Robin was Batman’s actual son! Superboy was Superman’s actual son! And they were both crazy dangerous kids and even more extreme opposites than their dads! It’s such an awesome concept and it actually happened.

I would say that Lois and Clark would never let their pre-teen son run off to the future alone, but the awful story which sent Jon off with Jor-El proved that wrong. I mean, logically they would never let that happen, but what do I know? I actually think everyone should have different speech patterns, too.

So what, exactly, did we get out of aging Jon Kent up? A teenage Superboy? Here’s the funny thing: Kon-El is back. So there are now two teenaged Superboys, so aging Jon makes even less sense.

Legacy?

Apparently, Jon is supposed to be the next Superman at some point and will surpass his father as the Superman. There is nothing about any of that that I like.

But it’s not really a big deal since it will never happen. This is comics we’re talking about. More specifically, this is corporately owned superhero comics we’re talking about.

This couldn’t have been done for Jon to take over his father’s role, then, even if that was some kind of a vague plan before Dan Didio left DC. I don’t care how much upheaval there is at Warner Brothers these days, no way they start their own streaming service and ax their most popular IPs at the same time.

The Super Sons are a great IP themselves, although Warner Brothers still owns that, of course. There are so many things they could do with that comic and those characters.

Even better, Superman and Batman being fathers created one of the best dynamics DC Comics has seen in years. There was so much potential there and we got to see so little of it.

Aging Jon Kent up on its own has meant very little, but when you add in the fact that it ended the Super Sons it makes the decision all the more unfortunate.